The Outer Layer

Managing Parallel Process in Complex Care Teams

Overview of the Outer Layer

Complex care teams often unconsciously mirror the very dynamics they aim to resolve in their clients in a phenomenon known as ‘parallel process’. These mirrored dynamics can impact professional relationships and undermine effective care, particularly when working with traumatised clients whose emotional states can become distributed across care systems. The Outer Layer is an attempt to create a shared language for these phenomena and what we can do to contain them. The approach describes a reflective boundary around care teams that helps identify, process, and transform these unconscious patterns. By drawing on individual ‘Care Team Consultants’ or multi-person ‘Governance Groups’ around care teams using existing resources, we wish to promote the use of structured reflective spaces for care teams. In this way, we hope more care teams can develop the capacity to use parallel process as valuable information rather than becoming entangled in it, ultimately providing more coordinated and effective support to complex clients.

Below, we outline the language we have developed to talk about parallel process dynamics in systems of care as well as a generalised model of intervention when these dynamics become problematic which we call The Outer Layer. This work is an attempt to put words to a practice we see across sectors – we do not propose to be inventing a radical new concept or to have a proprietary model generated through our work. Instead, we seek to create a platform to discuss work that is already happening in a deeper and more meaningful way. We see many services and practitioners across sectors who are working actively and effectively to contain parallel processes and support more integrated inter-professional practice for complex clients. With a shared language, we hope to support learning across these contexts to lead to better outcomes for complex clients across the developmental spectrum.

These ideas have been presented as a talk at the The Complex Needs Conference on the 26–27 March 2025 at the Grand Hyatt in Melbourne and will be presented at the International Child Trauma Conference (ICTC) on the 17 - 22 August 2025 at the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre.

Parallel Process

Systems mirroring stuck patterns

When we work with complex clients and families experiencing trauma and distress, something remarkable can happen within our care systems. The very dynamics that characterise our clients' struggles begin to show themselves within our professional relationships and organisational structures. This mirroring happens not through conscious choice, but through the natural human tendency to absorb and respond to the emotional fields we inhabit. This phenomenon, known as parallel process, represents one of the most challenging and often unrecognised aspects of complex care work.

We might conceptualise this process through the metaphor of pools of water that we each carry within us – reflective surfaces containing our feelings, reactions, and our state of connection with others. When we engage deeply with clients through empathic understanding, which is a cornerstone of effective human-focused work, an exchange of internal water occurs. In this way, we find ourselves holding portions of our clients' emotional experiences, their distress, fears, and defensive patterns. This unconscious exchange, while necessary for genuine understanding, can significantly alter our own internal state when it occurs with clients who are distressed and dysregulated.

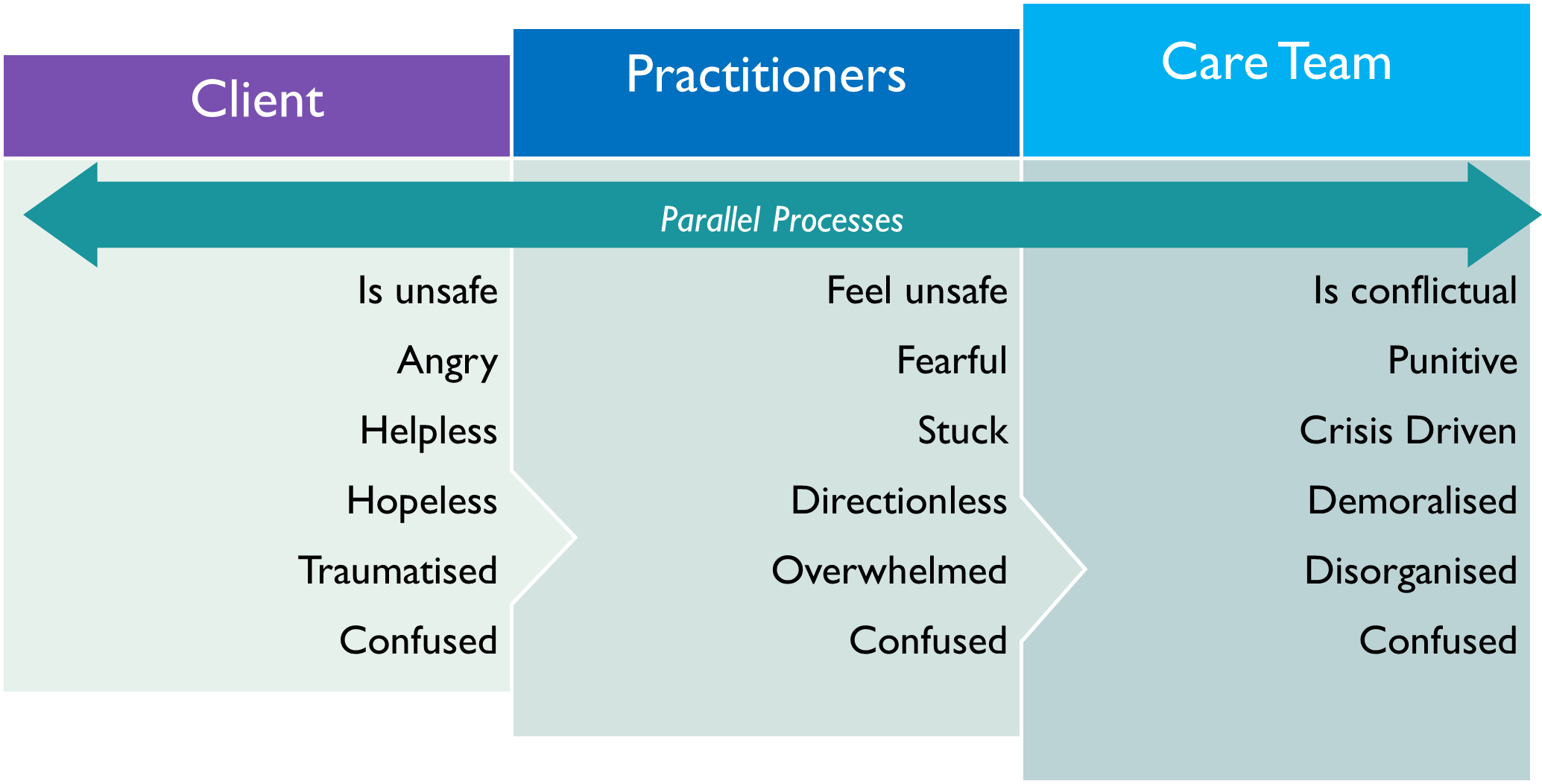

When our metaphorical waters become contaminated with our clients' turbulence, we may find ourselves experiencing feelings that weren't originally ours – fear, hopelessness, rage – the very experiences we're trying to help our clients process. Without awareness of this dynamic, we risk "acting out" these borrowed emotional states, becoming avoidant, defensive, or controlling in ways that mirror our clients' patterns. As our client’s distress becomes more complex, whether because of developmental trauma experiences, neurodevelopmental difference, or current contextual impacts, their internal states become increasingly fragmented. Different and sometimes contradictory emotional experiences may be projected onto different professionals within a care team. Then, when the care team meets, the state of the relationships within the professionals can come to mirror similarities and differences in professional mirroring of the client’s experience (as shown below in Figure 1).

Figure 1

Paralleled emotion and behaviour between clients, practitioners, and care teams. Adapted from the work of Dr Sandra Bloom on organisational parallel process.

This fragmentation, viewed through a systemic lens, creates a situation where each team member holds a different piece of the client's emotional puzzle, often believing their fragment represents the complete picture. If unmanaged, care team meetings can quickly transform into battlegrounds where professionals unconsciously project these contaminated emotional states onto one another – fighting over who truly understands the client, creating divisions that precisely mirror the client's internal fragmentation. These dynamics can then cascade through larger systems in a manner consistent with Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Supervisors can begin carrying the troubled waters of their involved staff, and whole organisations can develop murky reservoirs of unprocessed emotion. Practitioners throughout the system become cross-contaminated, carrying emotional material from cases they haven't directly worked with. The ecological interconnectedness of these systems means that disturbance at any level reverberates throughout the entire structure.

Patterns we’ve seen

Parallel process manifests when care teams unconsciously mirror the patterns, dynamics, and struggles of the clients they serve. In complex care settings, these parallel dynamics are particularly potent due to the intensity of client needs and the multiple systems involved. The following examples illustrate how specific client characteristics can become replicated in team dynamics based on our experience:

Rule Rigidity: When a client with a neurodevelopmental or interpersonal pattern of rigid adherence to rules over purpose is engaged with, this can mirror in a care team that becomes fixated on role boundaries and loses access to the necessary flexibility to attend to multifaceted needs.

Authority Echo: A client whose trauma history led to restrictive practices finds their lack of autonomy replicated when direct care staff have their decision-making authority removed, with routine decisions escalated to senior management at the expense of responsive practice.

Communication Breakdown: A client with significant communication difficulties triggers parallel patterns in the care team, who begin withholding crucial information or communicating in fragmented, unhelpful ways.

Emotional Volatility: When working with a client struggling to contain their emotional dysregulation, exhibiting unpredictable mood swings and intense reactions, the care team can begin experiencing volatile meetings with sudden emotional escalations, creating an atmosphere where members feel they feel the need to "walk on eggshells” with one another, not just the client.

Splitting Dynamic: A client with a fragmented attachment or personality system idealizes some professionals while devaluing others, becoming unconsciously replicates in the care team who forming in-groups and out-groups, with some members viewed as "good" and others as "bad" or incompetent.

Avoidance Pattern: With a client who shows consistent avoidant attachment, missing appointments and deflecting conversations from core issues, the care team may begin postponing difficult case discussions, leaving critical decisions unaddressed and avoiding necessary confrontation with system failures.

Rescue/Persecutor Cycle: A client from a chaotic family system who may repeatedly cycle between crisis and temporary stability could experience a care team mirroring this by oscillating between intense crisis intervention and periods of reduced engagement, creating a parallel pattern of inconsistent attention.

Learned Helplessness: A client with a protracted history of exposure to family violence or physical abuse presents as unable to take responsibility for small daily choices and may experience their care team exhibiting similar helplessness, referring decisions to external consultants or higher authorities rather than trusting their professional judgment.

The Outer Layer

Containing process through reflection

When care systems become saturated with client distress, professional boundaries blur and team members find themselves unwittingly enacting client patterns. This can be understood as the emotional distress of the client 'spilling out' through the care system in an uncontained way. The concept of wrapping an 'Outer Layer' around the care system draws on both systemic and psychodynamic traditions. This Outer Layer functions as a form of care team containment where a person or people outside the system help to hold and process overwhelming emotional experiences that has spilled into professionals. In complex care systems, this container must operate at a systemic level, providing a reflective boundary that helps process the team's collective emotional experience.

Figure 2

The Outer Layer conceptualised as an ‘exosystem’ through the lens of Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1977).

This containment function of The Outer Layer – which may be embodied by an individual consultant or a governance meeting structure – helps 'hold the water' of the group and allow for safe exploration around where things have gotten stuck. By establishing this meta-level perspective, the Outer Layer creates what would be called a "context for change" in Milan Systemic Family Therapy (Boscolo et al., 1987) – a space where established patterns can be observed, questioned, and transformed.

The Outer Layer can be useful in attending to several critical parallel processes, allowing correction:

First, it can help identify splits that have developed between team members or services, helping to integrate the fragmented understanding of the client that has become distributed across the system. This integration process in professional systems can be a therapeutic mirror to what we hope to facilitate for our clients – the ability to hold complex, sometimes contradictory experiences together in a coherent narrative.

Second, it allows disruption of service system re-enactments – stuck patterns where team members become trapped in repetitive, unproductive exchanges that often reflect the client's own past relational impasses. By naming these patterns and bringing them into conscious awareness, the Outer Layer helps free the system from these recursive loops.

Third, it can help to disrupt emotional contagion by creating space between emotional reactivity and professional response. This interruption allows team members to recognise when they are carrying projected emotions and to distinguish between their professional assessment and their emotional reactions.

Finally, it contains emotions that might otherwise overwhelm the care system's capacity for thoughtful response. This containment doesn't suppress emotional information but rather creates a vessel strong enough to hold it while its meaning is explored.

The time-limited nature of this intervention is crucial. The Outer Layer should gradually strengthen the system's own capacity to recognise and process emotional exchanges, transforming reactive patterns into collaborative understanding. Over time, this reflective function becomes internalised by the care team, becoming integrated into its own operations. This allows professionals to independently maintain clearer boundaries while remaining empathically attuned to the experiences of the client at the centre of the work.

The Outer Layer in Practice – Care Team Consultant

The Care Team Consultant represents a specific application of the Outer Layer concept – a role designed to embody the reflective and containing function needed when complex care teams become entangled in parallel process. Importantly, we propose this approach as not requiring additional resources as it can be implemented utilising existing senior roles with suitable expertise.

To be effective, the person introduced as the Care Team Consultant should hold a senior position within the care system as well as being someone with the skill to facilitate reflective discussion amongst an interprofessional group. For the consultant to be effective, their role must be transparently defined with the group – that is that the consultant explicitly names the system’s stuck patterns and seeks to help others notice how they impact on collaborative practice. To be truly effective, the Care Team Consultant should resist becoming a quasi-chairperson who simply directs the content of meetings. Instead, their focus must remain on facilitating reflective discussion and providing feedback on the dynamics they observe.

Figure 3

Features of the Care Team Consultant as an application of the Outer Layer similar to a Therapeutic Consultant in Milan Systemic Family Therapy (Boscolo et al., 1987).

The consultant might employ various models of reflective practice –the specific model matters less than maintaining focus on supporting the group to recognise and reflect on the parallel processes playing out in the system. In all cases, however, the time-limited nature of this role is essential. The consultant is not a permanent fixture and does not assume leadership of the care team but rather offers a temporary scaffold that helps the team develop its own reflective capacity.

When successful, the Care Team Consultant helps transform parallel process from an unconscious reenactment into valuable information about the client's experience. The team develops the capacity to recognise when they are being pulled into the client's emotional field and to use that awareness to deepen their understanding rather than becoming entangled in it. This provides containment for both the professionals and, ultimately, for the clients they serve, creating the conditions for a more connected response to complex needs.

The Outer Layer in Practice – Governance Group

The governance group represents an application of the Outer Layer concept – an approach designed to embody the reflective and containing function needed when complex care teams become entangled in parallel process at a systemic level. A governance structure refers to the framework that defines the authority, responsibility, and decision-making power within an organisation.

The membership of the governance group should consist of senior representatives from services involved in the Care Team who are empowered to make decisions together about their organisations function. Terms of reference should be developed that clearly outline membership, purpose and function of the group.

The establishment of a governance group serves 3 primary functions:

The governance group is removed from the day-to-day work with the client, creating space for them to reflectively think about how their organisations are contributing to splits and conflict within the care system. Each organisation should then provide feedback internally to address any identified parallel process.

To provide an outer layer of containment for each organisation through the investment at a senior level by providing reassurance and support to their staff engaged in direct work with the client.

To develop and promote a shared narrative for the client’s experiences and care.

The Outer Layer in Practice – Care System Coordination Plan

For the most complex cases where there are multiple and repeated parallel processes occurring within the care system, a considered and targeted intervention may be required to provide containment. This intervention may include the use of both a Care Team Consultant and a Governance Structure as well as any other approaches to addressing parallel process.

If multiple applications of the Outer Layer are being used, the development of a clear communication plan may be required to ensure there is transparency in communication and role clarity between each of the groups. With multiple applications of the Outer Layer occurring simultaneously, there is a risk that this could create a disconnect in communication and further exacerbate any parallel process. Developing a clear plan to provide an overall guide to the intervention, will support the care system to remain on track and clear in the purpose.

Figure 3

Phases and key considerations of a care system coordination plan

A Care System Coordination Plan should be time limited and timeframes for each phase of the intervention identified and shared with members of the care system. As the care system moves through each phase of the plan, consideration should be given to the sustainability of any change without intervention and the plan could be adapted as needed.

The Rainbow Practice Tool

This tool provides a visual framework for identifying, understanding, and disrupting parallel process dynamics within care systems. By mapping emotional patterns, behavioural responses, and relational dynamics across three interconnected layers, practitioners can recognise how challenges in one part of the system often manifest – either as replications or inversions – in adjacent layers. By explicitly mapping these dynamics, practitioners can:

Visualise otherwise hidden systemic patterns.

Increase awareness of how the systemic emotional responses mirrors the client.

Identify specific intervention points to disrupt unhelpful patterns.

Reduce burnout by understanding emotional response as systemic information.

Transform seemingly intractable problems by addressing their systemic nature.

Mapping Process Guide

Note: This can also be used as an individual reflective tool by ‘consulting internally’.

Facilitated Mapping Steps

Start at the centre: Ask the practitioner or team and talk about the client and their care. While they are, identify and note key emotional states, behaviours, narratives, or relational patterns observed in the client, the carers, and the care team that are prominent in people’s thinking – What is worrying people? What stands out?

Following initial reflection, look for connections across dynamics in each layer. It can be helpful during this phase to enquire about whether any identified dynamics prompt identifying a similar or opposite dynamic in an adjacent system. For each element, examine the adjacent layer(s) for:

Replicating patterns (similar dynamics across layers): Draw a connecting line with outward-facing arrows.

Inverted patterns (reactive, opposite dynamics across layers): Draw a connecting line with inward-facing arrows.

Look for clusters: Identify areas where multiple connections converge, indicating potent systemic dynamics. Also, look for conspicuously absent information and gaps.

Develop intervention strategies: Based on the identified patterns (including what’s missing), brainstorm specific approaches to disrupt unhelpful parallel processes.

Implementation Recommendations

Use a collaborative, curious stance when introducing the tool.

Normalise parallels as natural phenomena rather than indications of failure.

Invite team members to identify patterns they've noticed before offering observations.

Use mapping as a springboard for intervention planning, not just pattern identification.

Revisit and update the map in subsequent sessions to track system evolution.

References

Bloom, S. (2010). Trauma-organized systems and parallel process. In N. Tehrani (Ed). Managing Trauma in the Workplace – Supporting Workers and the Organisation (pp. 139-153). London: Routledge.

Boscolo, L., Cecchin, G., Hoffman, L., & Penn, P. (1987). Milan systemic family therapy: Conversations in theory and practice. Basic Books.

Bronfenbrenner, Urie (1977). "Toward an experimental ecology of human development". American Psychologist. 32 (7): 513–531.