Conservation of Resources in Systemic Practice

A Systemic Practice Guide to support Readiness for Therapy

Overview of COR in Systemic Practice

Conservation of Resources Theory provides a framework for understanding why some families struggle to engage with or benefit from traditional therapy approaches. The theory centres on the idea that families operate with various resource pools—including relational characteristics, family connections, tangible objects, and energy—and that stress occurs when these resources are lost, threatened, or fail to grow as expected. When families experience significant resource depletion or threat, they adopt a survival posture that prioritises protecting remaining resources over seeking new opportunities, which can manifest as resistance to therapeutic change or inability to attend therapy sessions. This survival stance is actually a rational response to resource scarcity, rather than simple non-compliance or lack of motivation.

To work effectively with these families, therapists must first help stabilise and rebuild resource pools through strategic interventions before attempting traditional therapeutic approaches. The process involves mapping existing resources, identifying areas of depletion, and systematically injecting resources while avoiding overwhelming the system, ultimately shifting the family from a loss-prevention mindset to one focused on growth and positive change. This approach recognises that successful therapy requires families to have sufficient resources to invest in the therapeutic process, making resource stabilisation a necessary foundation for meaningful therapeutic work.

These ideas have been presented as a talk at the Australian Association of Family Therapy Conference on the 3-4 July 2025 at the Pullman Hotel in Melbourne and you can download a PDF of the poster using the green button.

COR in Detail

The Challenge:

To understand why some families cannot make use of traditional therapy.

To understand this challenge fully, we need to recognise that there are essentially three distinct patterns of therapeutic non-engagement that professionals commonly observe. The first pattern involves families who simply cannot get to therapy sessions despite apparent willingness to participate. These families may miss appointments repeatedly, arrive late, or struggle to maintain consistent attendance even when they express genuine interest in receiving help. The second pattern encompasses families who do manage to attend therapy sessions but cannot sustain their participation over time, often dropping out after a few sessions or cycling in and out of treatment. The third pattern includes families who physically attend sessions and remain in treatment but seem unable to make meaningful use of the therapeutic process itself, appearing disengaged, defensive, or unable to implement suggested changes.

Through Conservation of Resources Theory, we can understand that, when families lack sufficient resources across the four key areas identified in the framework, they naturally adopt what the theory calls a survival posture. This survival posture creates a significant barrier to therapeutic engagement because therapy inherently requires families to invest various types of resources with no guarantee of return. Families must invest energy resources such as time, attention, and emotional bandwidth. They must risk relational resources by potentially disrupting existing family patterns or exposing vulnerabilities. They may need to invest material resources such as transportation costs, childcare, or time away from work. When families are already operating from depleted resource pools, these investments feel threatening rather than hopeful.

The key insight for professionals is recognising that therapist skill alone, while necessary, is insufficient when families lack the foundational resources needed to engage with and benefit from therapeutic interventions. Even the most skilled therapist using evidence-based approaches will struggle to create meaningful change with families who are in survival mode due to resource depletion. This understanding shifts the focus from trying to overcome resistance to strategically building the resource foundation that makes therapeutic engagement possible.

The Foundation of Conservation of Resources Theory

To truly grasp how Conservation of Resources Theory can transform our approach to family therapy, we need to start with its foundational principles and understand why this model offers such a powerful alternative to traditional stress theories. The theory emerged from Stevan Hobfoll's groundbreaking 1989 work, which fundamentally challenged how we understand human stress and motivation. Most stress theories at the time operated from what we might call a "breaking point" model - the idea that people function normally until pressure becomes too great, at which point they break down or malfunction. Hobfoll proposed something entirely different: that human behaviour is primarily motivated by our relationship to resources, specifically our drive to protect what we have and acquire what we need.

What makes this theory particularly relevant for family therapists is its inherently relational nature. Unlike individual-focused models that examine stress as something happening within a person, Conservation of Resources Theory recognizes that we exist within interconnected systems where resources are shared, protected, and sometimes competed for. This systemic perspective naturally aligns with how family therapists already think about human behaviour, but it provides a much more specific framework for understanding what drives family dynamics. The theory rests on several key principles that we need to understand deeply.

Principles of COR

The first principle states that resource loss is far more psychologically salient than resource gain. This means that losing something we value affects us much more powerfully than gaining something of equivalent value. This principle helps explain why families might cling to familiar but problematic patterns rather than risk trying new approaches that could potentially lead to improvement.

The second principle suggests that people must invest resources in order to protect against resource loss, recover from losses, and gain new resources. This creates what we might think of as a resource economy within families, where every action requires some form of investment with uncertain returns. Understanding this helps us see why families with limited resources might appear resistant to change - they literally cannot afford to invest in uncertain outcomes.

The third principle relates to resource pools. That is that the definition of "resources" in this context is both broader and more nuanced than its casual use. Resources aren't simply things we either have or don't have, like binary switches that are either on or off. Instead, resources exist in what we call "pools" with varying depths, and the depth of these pools determines what we can actually do with them. Consider money as an example that most people can relate to easily. We don't simply "have money" or "not have money" - we have varying amounts that enable different possibilities.

For example, if you have just enough money to cover your basic needs like rent and food, you have a shallow resource pool that leaves you vulnerable. Any unexpected expense could create a crisis, and you certainly can't invest money to create more money. If you have enough money to cover your basics plus some savings for emergencies, you have a deeper pool that provides some security and flexibility. If you have enough for basics, savings, and some extra for investments or discretionary spending, you have a pool deep enough to support growth and opportunity-taking.

Finally, the fourth principle relates to survival through gain and loss dynamics. The theory tells us that when people are not currently under stress, they naturally work to build resource surpluses as protection against future losses. This is why stable families often seem to keep growing stronger - they have enough resources to invest in continued growth. However, when families are under stress due to actual or threatened resource loss, their primary motivation shifts to minimising further loss rather than seeking gains.

Implications for Therapeutic Practice

This shift in motivation explains many behaviours that might otherwise seem puzzling or self-defeating. A family might refuse helpful services because accepting help feels risky when they're already operating from a survival position. They might stick with familiar but problematic patterns because changing feels like it could lead to additional losses they cannot afford.

The theory also recognises that failed investments - situations where we invest resources expecting gains but don't achieve the expected outcomes - can create stress similar to direct resource loss. This helps explain why families who have tried multiple therapeutic approaches without success might seem particularly resistant to new interventions. They've experienced the stress of investing precious resources without adequate return.

By understanding these foundational principles, we begin to see family behaviour through an entirely different lens. What might appear as stubbornness, resistance, or dysfunction begins to make sense as rational responses to resource scarcity or threat. This reframe opens up new possibilities for intervention that work with families' natural resource-protection instincts rather than against them.

Systemic Resource Types

While Hobfoll's original framework focused primarily on individual resources, your innovation here lies in recognising that families operate as interconnected systems where resources are shared, co-created, and collectively managed. This shift from individual to systemic thinking transforms how we understand both resource availability and resource threat within family contexts.

To fully appreciate this contribution, let's first consider why the original individual-focused resource categories, while valuable, don't quite capture the complexity of family systems. When we think about individual resources, we might focus on what each person brings to the family - their personal skills, their individual relationships, their own material possessions. But families are more than collections of individuals; they're dynamic systems where the whole becomes something different from the sum of its parts. Family resources emerge from the interactions, relationships, and shared experiences that exist between family members, not just within them.

This reconceptualisation creates four systemic resource categories that fundamentally centre the family as the unit of analysis while maintaining the depth and practicality that makes Conservation of Resources Theory so useful for therapeutic intervention. Let's explore each category in detail, understanding not just what it includes but why it matters for family functioning and therapeutic engagement.

-

Relational characteristics represent the internal capacities, patterns, and qualities that emerge from how family members relate to one another over time. These aren't individual traits that people bring to the family, but rather systemic qualities that exist in the spaces between family members and in their collective identity as a family unit.

Consider family traditions and rituals as an example of this resource type. A family's annual camping trip isn't just an activity - it's a relational resource that creates shared meaning, strengthens bonds, provides predictable connection points, and builds a sense of family identity that members can draw upon during difficult times. When this tradition is threatened or lost, the family doesn't just lose an activity; they lose a source of connection, meaning, and stability that helped them navigate challenges together.

The shared sense of humour that some families develop represents another fascinating aspect of relational characteristics. This isn't about individual family members being funny, but about the family's collective ability to find lightness and perspective together. This shared humour becomes a resource that helps the family cope with stress, repair after conflicts, and maintain connection during difficult periods. Families who have lost this capacity often describe feeling like they've "forgotten how to laugh together," which accurately captures the sense of resource loss they're experiencing.

Open communication patterns and emotional safety within the family system create perhaps the most fundamental relational resource. When family members can express themselves authentically, disagree constructively, and know they will be heard and valued, the family has developed a powerful resource for managing all other challenges. This communication capacity isn't just about individual skills, but about the family's collective ability to create and maintain emotional safety for all members.

-

Family connections encompass the web of relationships that exist beyond the immediate family but provide support, resources, and opportunities to the family system. These connections represent the family's integration into broader social networks and their ability to access support from extended relationships when needed.

Extended family relationships often form the backbone of this resource category. When grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins maintain active, supportive relationships with the family, they provide not just practical support like childcare or financial assistance, but also emotional continuity, cultural transmission, and additional perspectives on family challenges. The loss of these connections, whether through conflict, distance, or death, can significantly impact a family's overall resource capacity.

Community connections through religious organisations, schools, neighbourhoods, and activity groups provide families with a sense of belonging to something larger than themselves. These connections offer practical support during crises, social opportunities for family members, and reinforcement of positive family values and goals. Families who lack these connections often describe feeling isolated and unsupported, which accurately reflects their reduced access to this important resource category.

Professional relationships with healthcare providers, teachers, coaches, and other service providers who know the family well represent another crucial aspect of family connections. These relationships provide continuity of care, advocacy for family members, and specialised knowledge that supports family functioning. When families have positive relationships with professionals who understand their unique circumstances and history, they have access to resources and support that go far beyond what any individual professional interaction could provide.

-

The objects category encompasses the material resources that enable families to function effectively and protect their other resources. These aren't just possessions, but tools that help families achieve their goals, maintain their relationships, and weather difficulties together.

Safe, stable housing represents perhaps the most fundamental object resource for families. Housing provides not just shelter, but the foundation for all other family activities. When housing is unstable, unsafe, or inadequate, it affects every other aspect of family functioning. Family members can't focus on relationships, education, or personal growth when basic shelter needs aren't met. The quality and stability of housing also affects a family's ability to maintain other resources like family connections and relational characteristics.

Reliable transportation enables families to access other resources like employment, education, healthcare, and social connections. Without dependable transportation, families become isolated and unable to maintain the connections and activities that support their overall functioning. This isolation can quickly lead to losses in other resource categories as well.

Technology and communication tools have become increasingly important object resources for families. Reliable internet access, phones, and computers aren't luxuries but necessities that enable family members to maintain connections, access education and employment opportunities, and manage daily life activities. Families without access to these tools face significant disadvantages in building and maintaining other types of resources.

-

Energy resources represent the capacity that families have available to invest in protecting existing resources and developing new ones. Unlike other resource types that can be stored or accumulated, energy resources are often consumed in the process of being used, making them particularly precious and requiring careful management.

Mental and emotional bandwidth for problem-solving represents a crucial energy resource. Families need cognitive and emotional capacity to address challenges, make decisions, and work through conflicts. When this bandwidth is depleted by ongoing stress, trauma, or overwhelming demands, families lose their ability to address problems effectively, which can lead to cascading losses in other areas.

Quality time spent together without distractions represents an energy resource that many families struggle to maintain in our busy world. This time together is what allows families to build and maintain their relational characteristics, but it requires intentional investment of energy to create and protect. Families who can't find this time together often experience gradual erosion of their relational resources.

The motivation and hope that families maintain for their future represents perhaps the most important energy resource. When families believe in their ability to create positive change and maintain hope for better outcomes, they have the energy to invest in growth and improvement. When this hope is lost, families often enter the defensive posture described in later sections, focusing only on survival rather than growth.

The Interconnected Nature of Systemic Resources

Understanding these four categories requires recognising that they don't operate in isolation but form an interconnected system where resources in one category support and protect resources in others. Strong relational characteristics help families maintain their connections to external support networks. Adequate object resources provide the foundation for families to invest energy in relationship building. Diverse family connections provide both practical support and models for healthy relationship patterns.

This interconnectedness means that loss in one category can quickly lead to losses in others, creating the negative resource spirals that characterise families in crisis. Conversely, strategic investment in one category can create positive ripple effects that strengthen the entire resource system. By reframing resources in systemic terms, we create a practical framework for understanding family functioning that honours both the complexity of family systems and the practical realities that families face. This framework helps therapists think strategically about where to focus their efforts and how to sequence interventions to maximise positive impact across the entire family system.

‘Non-engagement’:

Survival posture as a rational response to resource threat

When we think about survival posture, it's helpful to use an analogy from the natural world. Consider how animals respond when they sense predators or environmental threats. They don't continue their normal foraging, playing, or exploring behaviours. Instead, they shift into a survival mode that prioritises immediate safety over all other activities. Their attention narrows to focus on the threat, their behaviours become more rigid and predictable, and they avoid taking risks that might expose them to additional danger.

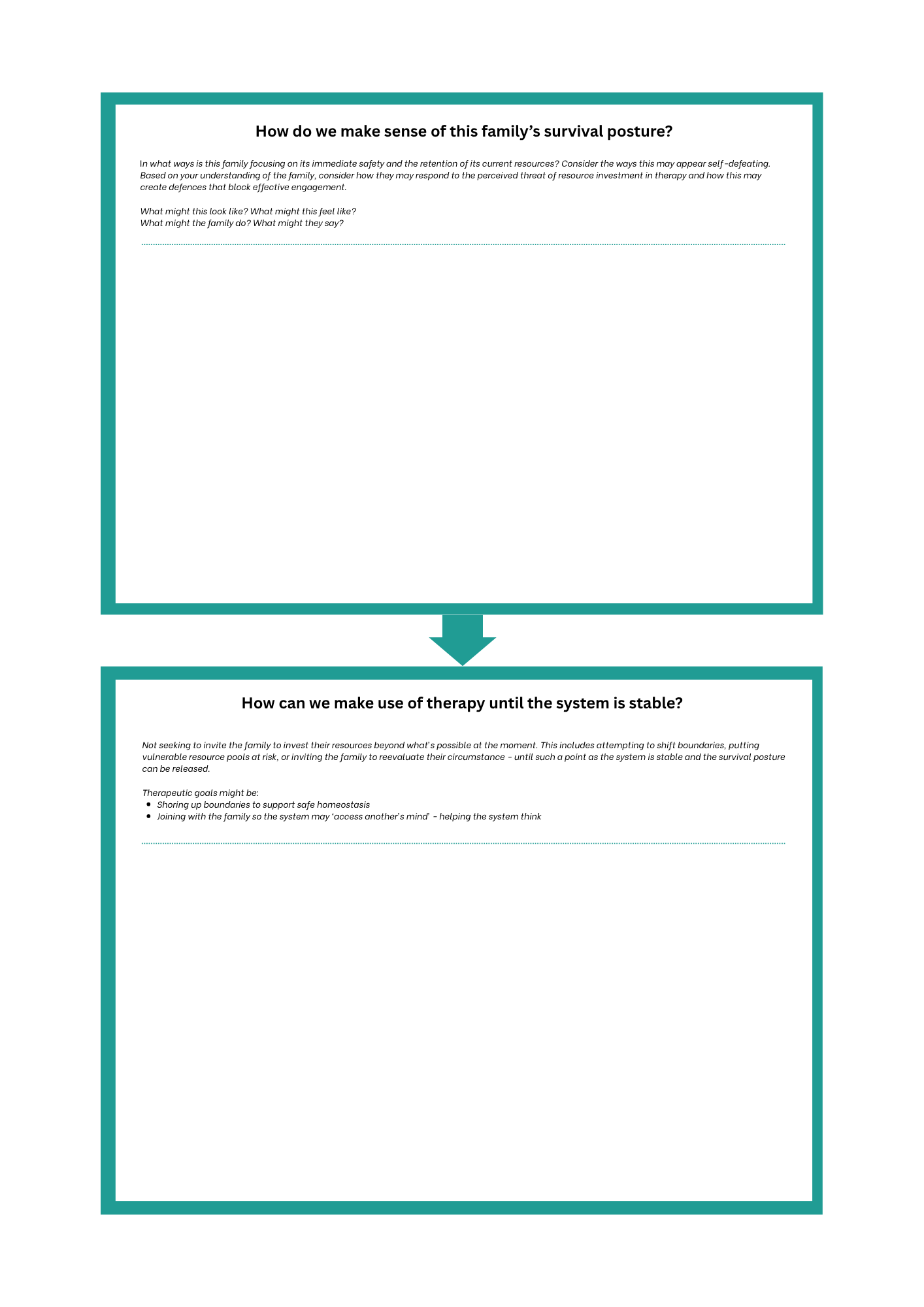

When a family system evaluates that its essential resources are under threat, have been lost, or that investments haven't yielded expected returns, the family naturally shifts into what we call a survival posture. This isn't a conscious decision or a character flaw, but rather an automatic systemic response designed to protect the family from further harm.

The key insight here is recognising that this survival response, while it may appear problematic from the outside, actually represents the family's best attempt to preserve what they have left. When we understand survival posture as adaptive rather than pathological, our entire approach to working with these families transforms. Instead of trying to overcome resistance, we begin to understand that we need to address the underlying resource threats that are driving the survival response.

Think about what happens to a family's functioning when they shift into survival posture. Their communication patterns often become more task-focused and less emotionally open, not because they don't care about emotional connection, but because emotional vulnerability feels too risky when resources are scarce. They may become more controlling or rigid in their interactions, not because they want to be difficult, but because predictability feels safer when everything else feels uncertain.

Shared Resource Hypervigilance

One of the most characteristic features of survival posture is the hypervigilant attention to potential threats that might lead to further resource loss. Families in this state develop what we might think of as a hypersensitive threat-detection system. They become acutely aware of any situation, relationship, or opportunity that might require them to invest precious resources with uncertain returns.

This hypervigilance affects how families process information and makes decisions. Instead of being able to consider the full range of options available to them, their attention narrows to focus primarily on avoiding potential losses. They may miss opportunities for growth or improvement because their mental and emotional energy is consumed by scanning for and protecting against threats.

From a therapeutic perspective, this hypervigilance explains why families in survival posture often seem to misinterpret neutral or even helpful interventions as threatening. When a therapist suggests that the family try a new communication technique, the family in survival posture doesn't hear an opportunity for improvement. Instead, they hear a request to invest precious energy and emotional resources in an uncertain venture that might fail and leave them worse off than before.

This narrowing of perspective is particularly challenging because it becomes self-reinforcing. The more narrowly focused a family becomes on avoiding loss, the more they actually do miss opportunities for gain, which can lead to gradual resource depletion over time. They may reject help, avoid taking positive risks, or stick with familiar but ineffective patterns because these choices feel safer in the short term, even when they're ultimately counterproductive.

The Paradox of Seeking Help while Resisting Change

One of the most poignant aspects of survival posture is the way it can create internal conflict for families. Many families in survival posture simultaneously want help and fear the process of receiving it. They may reach out for therapeutic services because they recognise that their current patterns aren't working but then find themselves unable to engage fully with the help that's offered.

This creates a painful paradox where families may feel frustrated with themselves for not being able to "do therapy right," while therapists may feel frustrated with families who seem to want help but won't accept it. Understanding survival posture helps both families and therapists recognise that this isn't a failure on anyone's part, but rather a natural response to resource scarcity that needs to be addressed before traditional therapeutic approaches can be effective.

The key insight is recognising that asking a family in survival posture to engage in traditional talk therapy is somewhat like asking someone who's drowning to participate in swimming lessons. The immediate need for safety and stability must be addressed before the person can focus on skill development and growth. Similarly, families in survival posture need their resource threats addressed before they can fully engage with therapeutic processes aimed at change and growth.

Implications for Therapeutic Practice

Recognising defensive posture fundamentally changes how we approach therapeutic work with families. Instead of interpreting resistance as something to overcome, we begin to see it as valuable information about the family's resource state. Instead of pushing harder for engagement when families seem resistant, we step back and consider what resource threats might be driving their defensive response.

This understanding also helps us recognise when traditional therapeutic approaches might actually be harmful rather than helpful. When families are in acute defensive posture due to overwhelming resource stress, attempting to engage them in reflective, insight-oriented therapy that challenges their existing patterns can increase their sense of threat and push them deeper into defensive mode. In these situations, the most therapeutic intervention might be helping to stabilise their resource base rather than attempting traditional therapeutic techniques.

Strategic Intervention for Sustainable Change

Think of this as the "how-to" guide that emerges from our deeper understanding of resources, survival posture, and family systems. What makes this approach particularly powerful is that it works with families' natural resource-protection instincts rather than against them, creating a collaborative pathway toward meaningful change.

To fully appreciate why this intervention approach works, let's first consider what happens when we try to apply traditional therapeutic methods with families who are in survival posture due to resource depletion. Imagine trying to teach someone to juggle while they're standing on unstable ground. No matter how skilled the instructor or how motivated the student, the foundational instability makes skill acquisition nearly impossible. The person will naturally focus on maintaining balance rather than learning new techniques. Similarly, families in survival posture due to resource threats cannot fully engage with therapeutic processes that require them to invest scarce resources in uncertain outcomes.

The intervention framework principles here recognise that sustainable therapeutic change requires what we might think of as proper sequencing. Just as you wouldn't start building a house by installing the roof, you can't effectively implement therapeutic interventions without first ensuring that families have sufficient resource foundation to support the work. This doesn't mean that traditional therapy is ineffective, but rather that it becomes much more effective when families have adequate resources to invest in the process.

Taking a Collaborative Systems Approach

One of the most significant shifts in this approach is recognising that systemic therapists often need to work beyond the boundaries of traditional therapeutic relationships to effectively help resource-poor families. This means engaging collaboratively with family services, schools, extended family networks, healthcare providers, and other systems that interact with the family. Rather than seeing this as outside the scope of therapy, we recognise it as essential therapeutic work that creates the conditions for successful therapeutic engagement.

This collaborative approach requires therapists to think strategically about which other systems and professionals need to be involved in supporting the family. It might mean working with a school counsellor to address educational resources for children, collaborating with family services to access material support, or helping the family strengthen connections with extended family or community supports. The therapist's role becomes that of a strategic coordinator who helps orchestrate resources rather than trying to provide all support directly through the therapeutic relationship.

For more information about working effectively and collaboratively in care teams, consider checking out another of our practice guides, The House Model of Care Teams.

Systemic Resource Mapping

Before any intervention can begin, we need to develop a comprehensive understanding of the family's current resource landscape. This isn't simply an assessment of what's wrong or what's missing, but rather a detailed mapping of existing resources that can be mobilised, areas where resources are shallow or vulnerable, and opportunities for strategic resource development.

The strengths-based analysis forms the foundation of this mapping process. Every family, no matter how depleted their resources might appear, has some existing strengths and resources that can be activated and built upon. These might be individual talents or capabilities, relationship connections that aren't fully utilised, community resources that the family doesn't know how to access, or internal family patterns that work well in some contexts but need to be expanded to others.

The analysis of vulnerable or missing resource pools requires careful attention to understanding which resource deficits are creating the most significant barriers to family functioning and therapeutic engagement. This isn't about creating a comprehensive list of everything that's wrong, but about identifying the specific resource threats that are keeping the family in defensive posture and preventing them from being able to invest in positive change. Sometimes the most critical resource deficit isn't the most obvious one. The resource framework helps us think systematically about these interconnections and prioritise our interventions accordingly.

Sequencing Resources Stabilisation

Once we have a clear map of the family's resource landscape, the next step involves what we call strategic resource injection. This process requires careful attention to sequencing, dosage, and integration to avoid overwhelming the family while creating sustainable positive change. When families have been operating in survival mode, sudden access to multiple resources can feel overwhelming rather than supportive.

Strategic resource injection often begins with addressing the most depleted resource pools first, particularly those that are creating acute threat and maintaining the family's defensive posture. If a family is facing imminent eviction, this housing threat will consume most of their mental and emotional energy, making it nearly impossible for them to focus on relationship building or skill development. Addressing the immediate housing crisis becomes the priority, not because housing is more important than relationships, but because the housing threat is preventing the family from being able to attend to their relationships.

However, the process isn't always as linear as addressing material needs first and then moving to relational needs. Sometimes relational resources need to be activated to help address material challenges. A family might have extended family members who could provide temporary housing or financial assistance, but old conflicts or pride issues prevent them from accessing this support. In this case, some relational work around reconnecting with extended family might be the key to addressing material resource needs.

The concept of "doses" of resources is crucial here. Just as medication needs to be given in appropriate doses to be helpful rather than harmful, resource injection needs to be calibrated to the family's capacity to integrate new resources without becoming overwhelmed. A family that has been socially isolated might benefit from reconnecting with one supportive relationship, but attempting to rebuild their entire social network simultaneously could feel overwhelming and actually increase their stress.

The Therapeutic Relationship as a Transitional Resource

During the period when families are holding defensive posture due to realistic resource threats, the therapeutic relationship itself can serve as a crucial transitional resource. However, this requires a fundamentally different approach to the therapeutic relationship than what we might use with families who have adequate resource pools.

With resource-poor families in defensive posture, the therapeutic relationship needs to provide co-regulation and system boundary support without demanding significant resource investment from the family. Think of this as the therapist temporarily lending their own regulatory capacity to help stabilise the family system while other resources are being developed.

The key is that this transitional use of the therapeutic relationship doesn't require the family to invest significant resources they don't have. They don't need to complete homework assignments, practice new skills, or engage in intensive emotional processing. Instead, they can simply experience being supported and regulated, which can help create the internal stability needed to eventually engage with more active therapeutic interventions.

The ultimate goal of this intervention process is helping families shift from a defensive, loss-prevention mindset to one that can consider growth and positive change. This shift doesn't happen through insight or willpower, but rather through the gradual stabilisation of resource pools that allows families to feel secure enough to take positive risks.

A family might start taking small positive risks, like trying a new approach to a recurring problem or being willing to explore a different perspective on an issue. They might begin to express hopes or goals for the future rather than focusing only on getting through immediate challenges. They might show increased flexibility in their responses to stress or demonstrate greater openness to feedback and suggestions. Once families have made this shift from loss-driven to gain-focused thinking, they become much more able to engage with traditional therapeutic interventions.

Integrating this with Traditional Therapy

Important, this resource-focused approach isn't meant to replace traditional therapeutic interventions, but rather to create the conditions where those interventions can be most effective. Once families have sufficient resources to support therapeutic engagement, evidence-based approaches to communication, conflict resolution, parenting, and individual mental health concerns become much more viable and effective.

The resource framework helps therapists understand when families are ready for different types of interventions and how to sequence therapeutic work for maximum effectiveness. Early work might focus on resource stabilisation and defensive posture reduction. Middle-phase work might involve skill building and pattern change. Later work might focus on growth, goal achievement, and relapse prevention.

By understanding intervention through the lens of resource management, therapists can work more strategically and effectively with families who have previously been difficult to engage or help. The approach honours families' natural protective instincts while creating pathways for sustainable positive change that builds on their existing strengths and addresses their actual barriers to growth and stability.

Resource Mapping Tool

Formulating Cases using the COR Practice Tool

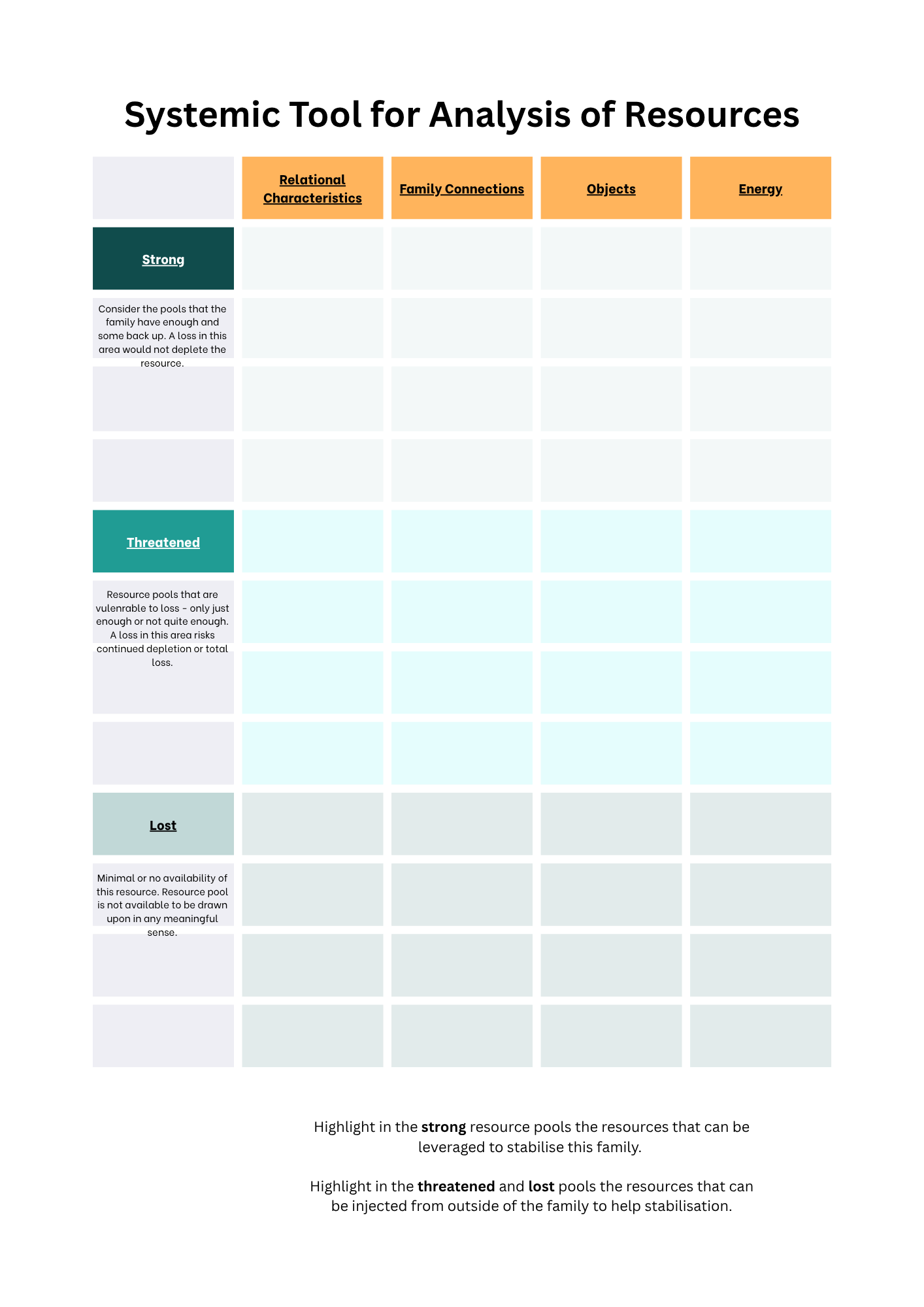

The Resource Mapping Practice Tool is a comprehensive assessment framework designed to help family therapists, case managers, and therapeutic specialists systematically analyse family resource states and develop strategic intervention plans. This tool translates Conservation of Resources Theory into practical application, providing a structured approach to understanding why some families struggle to engage with traditional therapeutic services and how to create more effective intervention strategies.

The tool guides practitioners through a five-step process that moves from assessment to strategic planning, ensuring that therapeutic interventions are matched to families' actual resource capacity rather than their presenting problems alone. By mapping resources across the four systemic categories (Relational Characteristics, Family Connections, Objects, and Energy), practitioners can identify both strengths to leverage and vulnerabilities that require attention before traditional therapeutic work can be effective.

When & Why to use the Resource Mapping Tool

The Resource Mapping Tool addresses a fundamental gap in traditional assessment approaches by shifting focus from pathology identification to resource analysis. By systematically mapping resources, practitioners can avoid the common pitfall of recommending interventions that families cannot realistically implement due to resource constraints. This leads to more realistic treatment planning, better therapeutic engagement, and ultimately more successful outcomes.

The tool is particularly valuable when working with families who present with patterns of therapeutic non-engagement, frequent service use without sustainable change, or what appears to be resistance to help. It's also valuable for families who have had previous unsuccessful therapeutic experiences or who present with complex presentations that don't respond well to standard interventions.. It should be used early in the therapeutic process, ideally during initial assessment phases, to inform case conceptualisation and treatment planning decisions.

The assessment process itself can be therapeutic, as it helps families recognise and articulate their existing strengths while developing a clearer understanding of their challenges. This can reduce the shame and frustration that families often feel when they've been unable to benefit from previous therapeutic attempts, replacing self-blame with a more systemic understanding of their situation.

How to use the Resource Mapping Tool

Step 1: Comprehensive Resource Mapping Begin by systematically exploring each of the four resource categories, identifying what resources are strong and stable, which are threatened or vulnerable, and which have been lost. This requires moving beyond surface-level assessment to understand the depth of resource pools in each area. Ask specific questions to their family and their other supports about how the family relate to one another (and services), support and social networks, their material resources, and energy levels, paying attention to both current states and recent changes.

Step 2: Identifying Leverage Points Once you've mapped resources across categories, identify the strongest, most stable resources that could be activated to support system stability. These might include a close relationship with an extended family member, a family's strong problem-solving skills, stable housing, or a parent's resilience and determination. These resources become foundational for intervention planning.

Step 3: Prioritizing Vulnerable Areas Examine the threatened and lost resources to determine which deficits are most critical for system stability and which might be addressed through external supports or services. Consider how losses in one category might be affecting other areas and which resource deficits are most directly contributing to the family's defensive posture.

Step 4: Understanding Defensive Posture Synthesise your resource mapping to describe the specific survival strategies this family has developed in response to their resource situation. Consider how their defensive posture might appear in therapeutic settings and what interventions might feel threatening versus supportive to them. This step helps formulate how the family might respond to different therapeutic approaches.

Step 5: Strategic Therapeutic Planning Develop intervention strategies that work with the family's resource state rather than against it. For resource-depleted families, this might mean focusing on co-regulation and boundary support rather than insight development. For families with adequate resources, traditional therapeutic approaches may be appropriate. Consider sequencing interventions to build resource stability before addressing more complex therapeutic goals.

Maximizing Tool Effectiveness

To use this tool most effectively, practitioners should approach it as a collaborative process rather than an expert assessment. Involve family members in identifying their own resources and challenges, as this increases accuracy and helps families develop their own resource awareness. The mapping process should be ongoing rather than a one-time assessment, as resource states can change rapidly based on life circumstances.

Consider using the tool in team consultations or supervision to develop more comprehensive resource maps and intervention strategies. Different team members may identify resources or vulnerabilities that others miss, and collaborative planning can lead to more creative and effective interventions.

Remember that resource mapping is not about fixing deficits but about understanding the system well enough to work strategically with existing resources while carefully building capacity for growth. The goal is creating sustainable positive change that builds on family strengths rather than overwhelming them with interventions they cannot realistically maintain.

By using this tool systematically, practitioners can develop more nuanced, effective approaches to family work that honour both the complexity of family systems and the practical realities that families face in their daily lives.

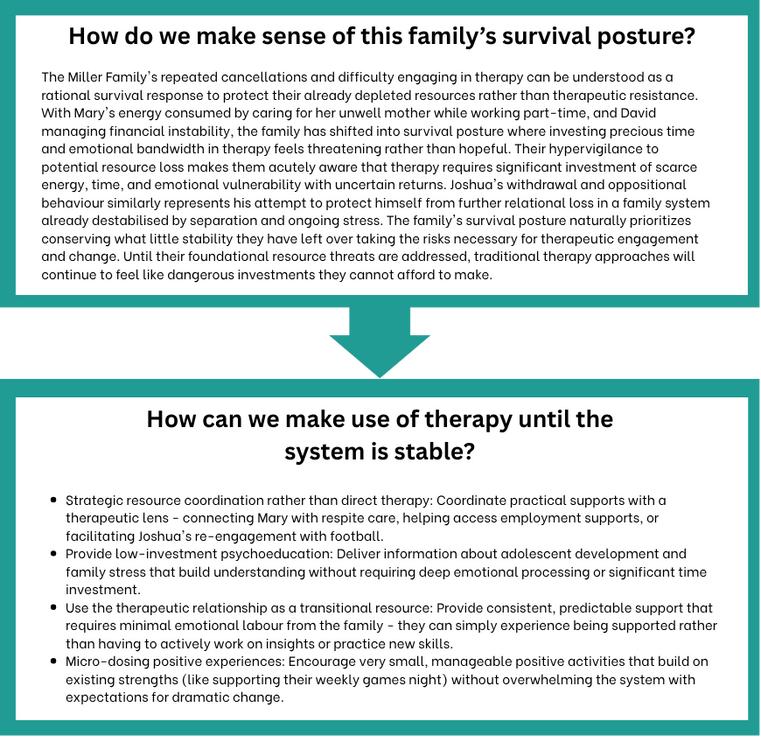

Case Study 1: The Miller Family, coparenting after divorce

Joshua is 13 years old and lives in a 50/50 shared care arrangement between his separated parents, Mary and David, following their divorce one year ago. The family was referred for therapy due to concerns about Joshua's declining academic performance, cannabis use, and increasingly oppositional behavior. Despite initial engagement, the family has repeatedly cancelled sessions, citing difficulties finding time due to work responsibilities and Mary's caregiving duties for her unwell mother. The care team described feeling uncertain about how to support this family's therapeutic engagement.

Joshua's Presenting Problems

Declining academic performance since parental separation.

Cannabis use experimentation.

Increasingly oppositional and irritable behaviour toward parents.

Loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities (football).

Depressive symptoms including poor concentration, amotivation, and sleep difficulties.

Social withdrawal from family relationships.

Family Strengths

Both parents maintain good intentions toward Joshua's wellbeing.

Strong co-parenting commitment evidenced by maintaining shared care arrangement.

Joshua has maintained positive peer relationships with two close friends.

Extended family support available through David's sister and brother-in-law.

Both parents have established, long-term friendships.

Family capacity for playful connection (positive memories of games and movies during COVID).

Previous ability to provide stable schooling environment.

Help-seeking behaviour and initial therapeutic engagement.

Important History

Three years of volatile marital conflict prior to separation, including episodes where parents would leave the house.

David's employment instability over five years creating financial stress.

COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted family through isolation, employment disruption, and educational challenges.

Mary's mother's illness requiring Mary to reduce work to part-time and take on caring responsibilities.

Limited extended family support due to aging and unwell grandparents.

Financial strain from maintaining separate households in same region to preserve Joshua's school stability.

Recent deterioration in parent-child relationships with increased withdrawal and rebellious behavior.

Formulation of the Miller’s Case using the COR Mapping Tool

Applying this to the Case of the Millers

Recommendations

To support Mary and David to focus on cognitive tasks that allow for some relief of engaging in emotionally heavy conversations through provision of psycho-education about adolescent development, stressors that can occur in families during this developmental transition and ways in which rules and boundaries can be adjusted to allow for increased flexibility. This could also be done by providing information sheets.

To encourage Mary and David to explore opportunities for re-engagement in playful activities with Joshua such as movies, games etc that can promote their relational connection.

To encourage Mary and David to explore how Joshua’s friends' parents, aunt and uncle may be of support with regards to promoting increased energy through tasks such as school drop-offs, pick ups, cooking etc.

To explore Joshua’s relationship with his football coach and how they may be able to move towards Joshua to build on their relationship and support his re-engagement in football.

To explore the capacity to offer morning, evening or online sessions.

Outcomes

Both Mary and David worked towards setting up a games night on the weeks that they had Joshua in their care, noting an increase in playfulness and felt sense of connection with their son. (strategic injection of resources)

David felt able to speak with his sister, which resulted in an offer for her to pick up Joshua once a week and spend time with him at her home. This increased Joshua’s relational connectedness whilst also offering both Mary and David an evening of respite providing them time and energy to put towards engaging in parent sessions, initially on a monthly basis. (strategic injection of resources)

Through engagement in parent sessions, both Mary and David expanded their awareness of adolescent development and developed insight into the contributing factors to stress in their family. This supported increased empathy towards themselves, each other and David and supported their application of flexibility in rules to meet the developmental stage of the family system. (shift from loss-driven to gain-focused)

Following these changes, Joshua’s mood improved and his adolescent exploration reduced in risk. Conflict in both homes lessened and the family no longer felt they needed service intervention.

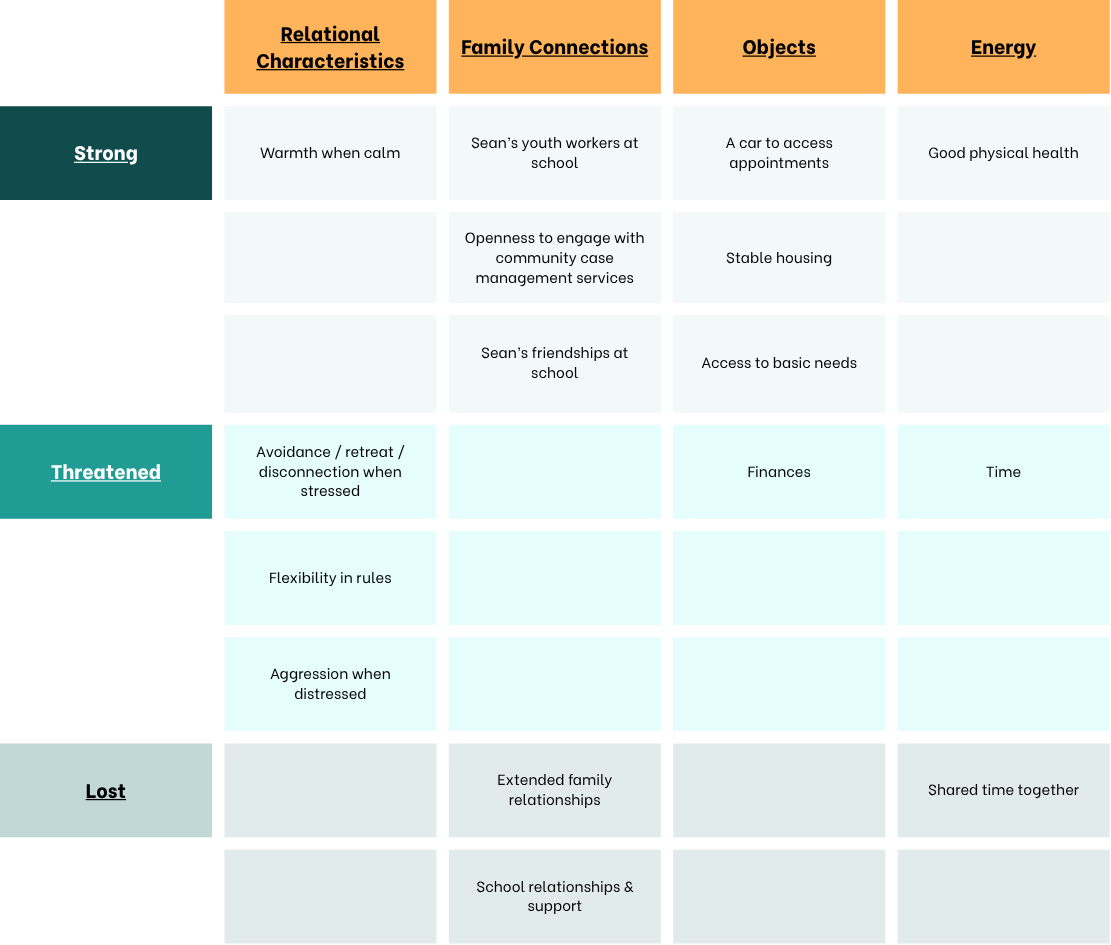

Case Study 2: Sean & Hilda, kinship care

Sean is 13 years old and lives with his maternal grandmother, Hilda, after having been removed from parental care due to protective concerns. His care team requested a consultation to better understand problems in Sean’s behaviour and how to support Hilda. The care team reported Hilda presented as highly stressed and overwhelmed by Sean. A recent referral had been made to a clinical service that offered therapy to kinship carers, however Hilda had cancelled multiple appointments stating that she was unable to attend due to her work and ongoing fatigue. The care team around Sean and Hilda described feeling ‘stuck’ when considering what services would promote the stability of the current placement.

Sean’s Presenting Problems

Verbal and physical aggression towards children and adults, including Hilda.

Multiple suspensions from school leading up to a recent expulsion.

Interpersonal sensitivity and hypervigilance.

Complex grief and loss.

Some difficulties with trusting others.

Family Strengths

Sean is achieving academically at an ‘expected’ level.

Sean has good engagement with two youth workers at school.

Sean has pro-social friendships focused on skateboarding and gaming.

Hilda showed consistently good intention to provide care needs in the home.

Hilda and Sean’s relationship showed warmth when stress in the home was low.

Important History

Sean’s father died when he was a child.

Sean’s parents struggled to be attentive and attuned to him, resulting in cumulative emotional harm.

Harm to Sean included exposure to family violence, parental substance use, environmental neglect, and emotional neglect.

Sean was ultimately relinquished by his parents and thus entered kinships care.

Sean’s broader family relationships are characterised by hostility and aggression.

Intergenerational trauma contributing to a closed family system that was mistrustful of services.

Formulation Sean’s Case using the COR Mapping Tool

Applying this to Sean’s Case

Recommendations

For the care team to support Hilda to engage in therapeutic support by decreasing stressors and limitations in resources such as time and energy. This could be through collaboratively problem solving around tasks such as school drop offs/pick ups/cleaning by engaging additional supports and allows for the opportunity for her to experience professionals as competent and capable.

For the care team to offer psychoeducation regarding adolescent development to support Hilda’s insight into the need for adjustment in caregiving. Specifically for this to be with regards to flexibility and negotiation that will promote Sean’s independence. For the intentionality around this task to be extended towards her accessing additional external resources through experiencing respite if there can be compromises regarding him engaging in developmentally nourishing activities such as spending time with his friends.

For Case Management to support grandmother to identify opportunities to engage in meaningful relational connection with Sean that can occur in a manner that is unconditional (for example; watching a movie once a week, eating dinner together) to continue to promote their connection and build on safety in their relationship.

Outcome

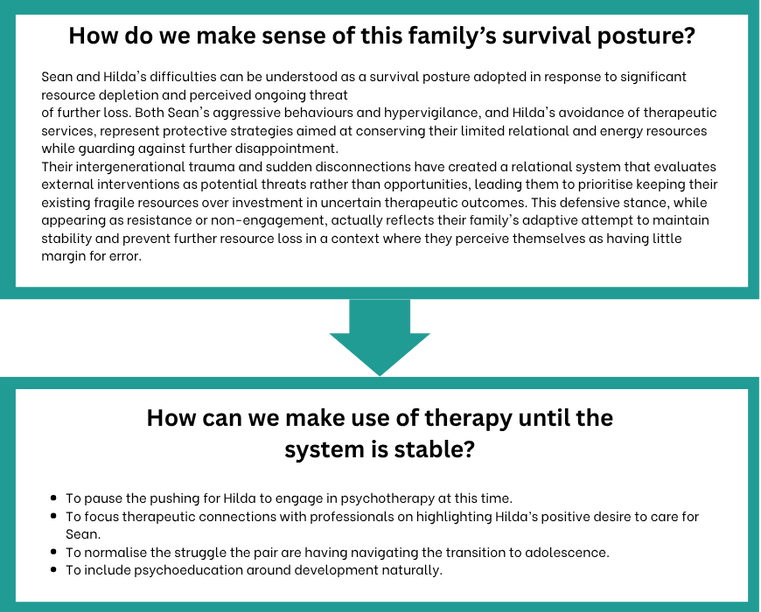

The care team were able to engage with Hilda to identify barriers to engaging in therapy. In particular, both time and energy (internal and relational) were important in addressing her survival mindset. These led to her fearing additional loss through missing work and an overwhelm around the tasks associated with caregiving and running a household.

The team paused their encouragement for Sean’s grandmother to attend therapy and suggested they address the barriers to her being able to engage. (avoid over-resourcing)

The team were able to access carer support that came to her house once a week to clean and a gardener who came monthly. (strategic injection of resources)

The team were able to engage in conversations about adolescent development to support Hilda to better understand his psycho-social needs including independence and autonomy - this led to him spending one night a week at a friend’s house, which gave Hilda additional time, allowing her to internally refuel. (strategic injection of resources)

Sean and his grandmother negotiated having at least one dinner together a week. (shift from loss-driven to gain-focused)

Following these changes, Hilda approached the care team to ask if she could re-start therapy. She said she had reflected on the positive changes in Sean’s behaviour, and noted that he hadn’t had any suspensions at his new school. Hilda reported feeling ‘closer’ to Sean and wanting to work on building this up further.